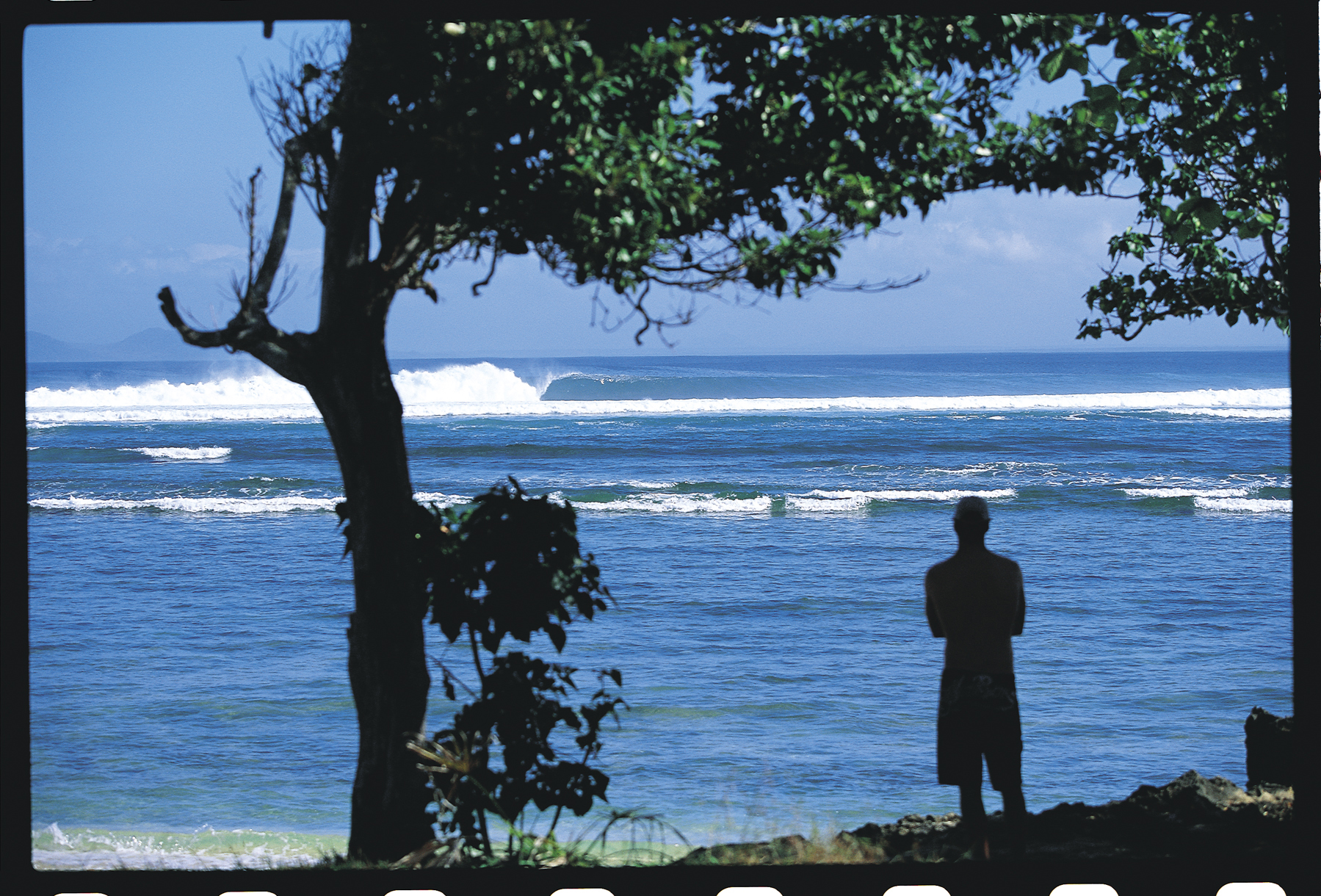

G-Land © Andrew Shields

Grajagan or G-land is one of the sickest waves in the world. It’s fairly remarkable for swell consistency and for offshore winds, but the rest of the variables are sometimes not as agreeable. Swell direction can be a problem, as can the tide. Crowds can be outrageous at times, and the obligatory selfish Brazilian pack sometimes arrive and can run rampant all over the wave and the camps. But sometimes you luck on and get it uncrowded and good, and it’s like no wave on earth.

We’re back in the jungle and it’s weird in here. As much as man tries to push it back, so the jungle forces its way forward. It’s a hopeless battle, like trying to stop a shifting sand dune. It’s relentless and remorseless and eventually you just know that nature is going to win. The jungle densely closes over the footpaths, trees fall over all the time, get caught up in branches and are left hanging.

Monkeys crash through the jungle and then sit and watch you patiently. They watch from their domain, their kingdom, as you nervously scan the ground in front of you for snakes and scorpions, keep your eyes open for jungle badgers. Wild pig sightings are rare, as are those of the black puma. Mosquitoes are rampant, and malaria lurks. Rats gnaw at your losman all night, wanting to eat your soap. Sea-snakes, stonefish and dugongs await you in the water. In this part of the world, eastern Java, nature reigns supreme.

The wave has been re-discovered, and new sections have come to light in extreme tides and swell directions. In-between the well-known sections like Kongs, Moneytrees, Launch Pads and Speedies there’s now The Fang, The Ledge and Quiksilvers. Not forgetting Chickens and Twenty-Twenties. But still the coral remains ever present. Shallow and sharp, it beckons at every bottom turn, it smiles at you every time you slip behind the falling lip of a barrelling wave. It grabs for soft bare feet and clutches for office hands stroking in shallow water. A reef cut is bad news in the tropics. The infection that inevitably results can be treated and despite being cleaned, never seems to actually heal until you get out of the humidity. The jungle humidity hangs on you like a warm, wet blanket. Any body movement results in a break-out of sweat.

There are other dangers on land. Western dangers brought over with Boyum and Lopez and all the others who dreamed of a surfing monastery in the jungle all those years ago. A monastery dedicated to the appreciation of one of the finest waves in the world. These dangers are the foibles of being a human. The modern addictions. Civilised cravings, like beer, whiskey, cigarettes, painkillers and sleeping pills.

When the surf is flat the beer flows. Along with the beer comes the obligatory cigarettes, left over from ‘social smoking’ habits in the cities and nightclubs. Clove cigarettes, indigenous to this land, are smooth tasting and leave a sweet memory on the lips. They are artificially soft on the throat, which hides the carcinogens roaring through and sticking onto your clean lung tissue. The sun slips down early on the equator and it is pitch-black by six o’clock. So black that you can’t see your hand as you pee into the jungle. Sometimes you see a pair of unmoving, unblinking eyes staring back at you. Paranoia here is known as the jungle jitters, and invariably leads to the sleeping tablets, the doormen at the club of bad dreams.

The only thing that can keep you away from all of these civilised dangers is the surf. The physical and mental distraction of solid, grunting waves reeling down the point.

Our first days floated by on a wave of malaria medication. The waves were small, we were tired, jet-lagged and still finding our groove with the people and the environment. Time has little meaning on the edge of reality, and my watch had stopped working. Our heart rates slowed down and our bowel movements sped up. The jungle diet passes through you fairly quickly.

Along with all the exercise we were getting we actually started feeling good after a while, so we doused this feeling with beer. We played pool and we drank a few beers every night. We saw a couple of jungle creatures. Then the swell jumped to 12 foot overnight and went out of control. We watched, languidly, from the shade of a tiny tree on the water’s edge as the jungle exhaled heated offshore breath out to sea. Some guys tried to surf, but the wash was impossible. Mission not accomplished.

Two sleeping tablets later and it was miraculously morning again, and it was pumping! Six to eight-foot and round! A fierce rip left over from the previous days massive swell a constant reminder and irritation as we hooked into perfection. One real wave at Speed Reef is all you need to wash away the stink of the city, to cleanse your soul. Just one of these waves is a fair trade for the last six months spent stressing about someone else’s business.

It’s a serious wave, and your body reacts accordingly. Adrenal glands start squirting crazily, heart rates quicken and endorphins move around and hit receptors. Lucidity roughly pushes jungle sluggishness aside as giant sets loom on the bommie and threaten to break outside and wash everyone over the reef. One mammoth set catches us, and boards and safety concerns are flung aside as we swim deep! Breathless, with eyes popping, we regain our position in the lineup with just a little more care.

After the session the mood of the camp changes dramatically. There are excited faces. Some people are talking about the big set, or about someone’s sick backhand barrel. People are examining their boards; getting bigger boards ready just in case. We head straight for the bar.

For the rest of our nine days the waves pump. Ranging from four to eight feet, they never let up. We would wake up in the morning, go through the breakfast/ablution motions, and get ready for the late morning’s trade winds to kick in. They kick in everyday. It’s just a matter of when. We surf until we are chafed, sunburned, arms weak and sore from paddling. Still the waves pour through.

Our trip has been characterised by an afternoon low tide, so the late mornings are spent furiously getting as many waves as possible as the trades puff. As the tide drains out over the afternoon hours we chill and watch, sipping on our beers. Some guys surf through the low tides and the harsh afternoon glare of the dropping sun. It’s not as good but it’s so uncrowded. One of the best waves in the world and about five guys surfing it.

We’ve emptied the beer fridge every night, but we’ve surfed every day, so it’s a fair trade. The jungle has a mollifying spirit that envelops you and seems to make all these outrageous waves and occurrences seem normal and commonplace.

Our last day and the waves are still going off, and we’re back out there. We surf until we can’t surf anymore. Until we are sated. Until we know that we could go, if necessary, for a few weeks without another surf. Or so we believe.